According to a study, women who did not take a prenatal vitamin each day before as well as throughout the 1st month of pregnancy had almost double the risk of having a child with an autism spectrum disorder compared to women who took a prenatal vitamin each day, and when coupled with a high-risk genetic makeup, the associated risk was 7 times greater.1✅ JOURNAL REFERENCE

DOI: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31821d0e30 The consumption of prenatal vitamins could be especially effective for mothers with a genetic susceptibility. For women who took prenatal vitamins and had a particular high-risk genetic makeup, the estimated risk of having an autistic child was up to 7 times greater in comparison to women who had a more favorable genetic makeup and who took prenatal vitamins.

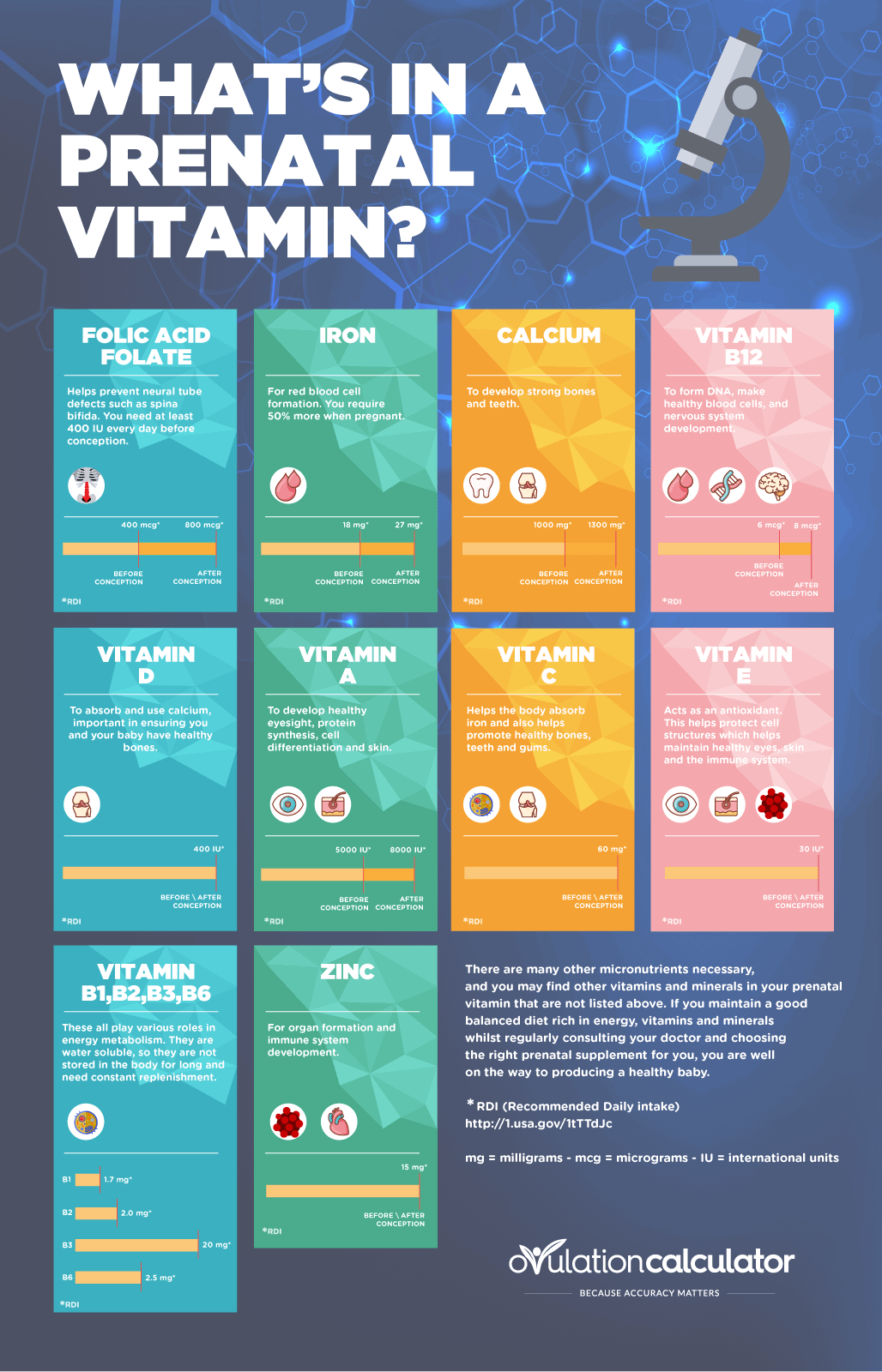

The researchers suggest that the synthetic kind of folate, known as folic acid, and the other B vitamins found in prenatal vitamins probably protect against early fetal brain development deficits. Folate is proven to be vital to neurodevelopment and research has revealed that folic acid supplementation could potentially prevent as much as 70% of neural tube defects.

Data was collected from about 700 families with 2 – 5 year old children who took part in the CHARGE (Childhood Autism Risk from Genetics and the Environment) study and had typical development or autism.

Women who took part in the CHARGE study were telephonically questioned whether or not they took multivitamins, prenatal vitamins or other supplements anytime throughout the 3 months before and throughout their pregnancies, as while as while breastfeeding. Whenever the respondent reported having taken vitamins, she was also asked which kind she took, at what frequency and dosage and in which months of pregnancy they were taken.

The year the child was born and maternal education were accounted for; results were the same when the age of the mother was also accounted for. There was however no difference between mothers taking or not taking prenatal vitamins after the 1st month of pregnancy. This suggests that, by the time the majority of women are aware of their pregnancy, there may not be any benefit of prenatal supplements for the child with regards to autism risk.

Interaction effects were significant for 2 maternal genes, which included a well researched variant on the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene linked to increased levels of the amino acid homocysteine and less efficient folate metabolism.

Mothers of autistic children were 4.5 times more likely to have both the less efficient methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase 677 TT genotype and to have not teken prenatal vitamins throughout the conception period compared to mothers of typically developing children.

Increased autism risk was also linked to other maternal gene variants related to less efficient one-carbon metabolism, but only when the mother did not take the prenatal vitamins in the early months before and immediately after conception.

Also, being homozygous for a common variant in the child’s COMT (catechol-O-methyltransferase) gene was linked to over 7 times the estimated autism risk in mothers who did not take the supplements around conception time, in comparison to children with other genotypes whose mothers did take periconceptional prenatal vitamins.

COMT enzyme activity is reduced by this gene by 3 to 4 times. The COMT enzyme is activated during early neurodevelopment, and is well known for the part it plays in dopamine degradation. Differences in functional and structural brain have been defined across COMT genotypes, especially in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, areas affected by autism.

Image Source – ovulationcalculator