According to a study, women who breastfeed for 6 months or more have almost half the risk of type 2 diabetes during their childbearing years. The study revealed a significant association between duration of breastfeeding and reduced risk of diabetes, even after all other possible risk factors were accounted for. Women breastfeeding for 6 months or longer after all births had a 47% reduced risk of type 2 diabetes in comparison to women not breastfeeding at all. Those breastfeeding for 6 months or less had a 25% reduced risk of diabetes. Data was analyzed from the CARDIA study 30 year follow up.[1]

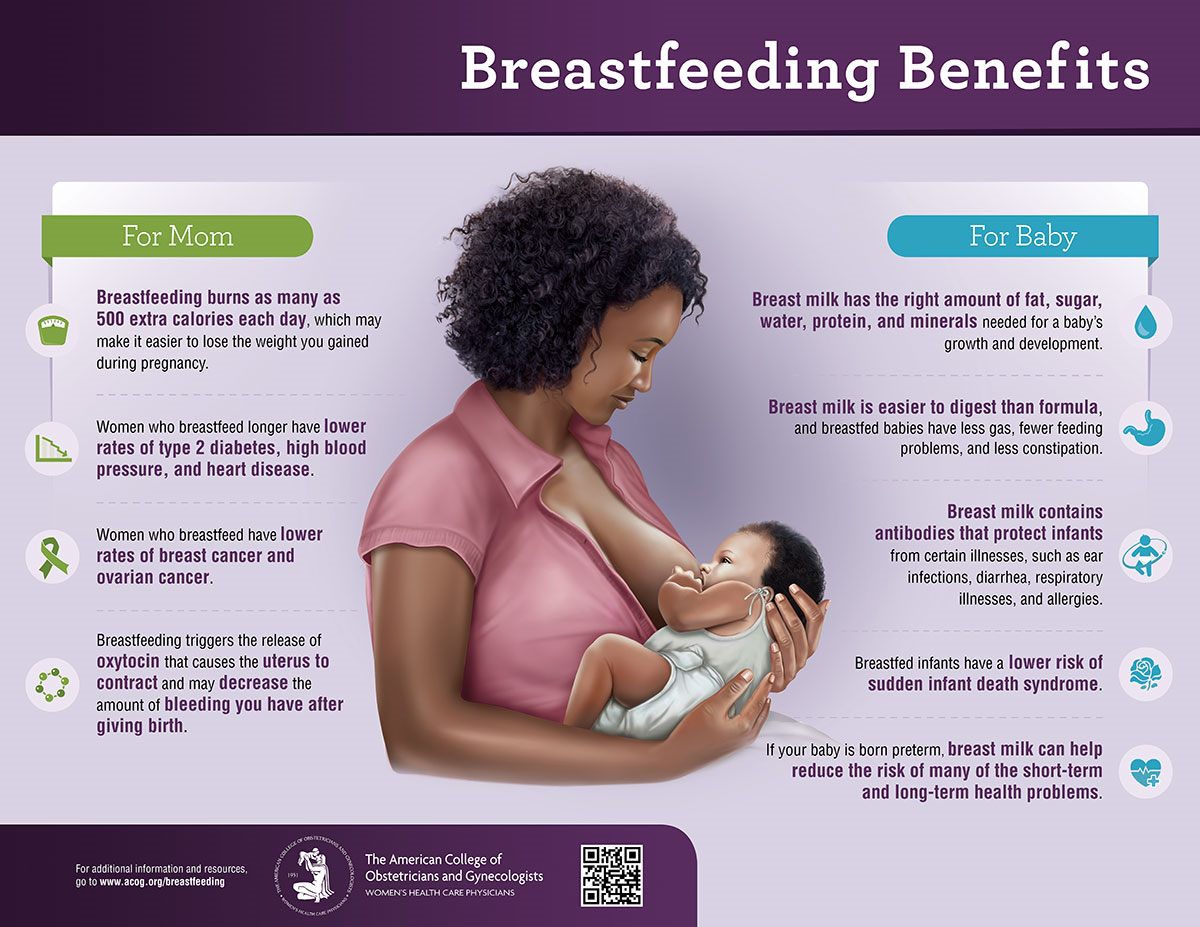

These findings add to the increasing evidence of the protective effects that breastfeeding has for mothers as well as their children, which includes reducing the risk of ovarian and breast cancer for the mother. Diabetes incidence decreased proportionately as duration of breastfeeding increased, regardless of gestational diabetes, race, body size, lifestyle behaviors, as well as metabolic risk factors taken into account prior to pregnancy, which implies that it’s possible the underlying mechanism could be biological. A number of probable biological mechanisms exist for breastfeeding’s protective effects, which includes how the hormones associated with lactation influence the pancreatic cells which control levels of blood insulin and thus influence blood sugar.

It’s been known for some time now of the many benefits for both mothers and their offspring that breastfeeding has. This study now shows strong protection for mothers breastfeeding for months after delivery, with a possible reduced risk of type 2 diabetes by up to a half as they get older. The study participants were 1,238 women without diabetes when enrolling in CARDIA, or before their ensuing pregnancies. Each participant had at least 1 birth over the course of the next 30 years and was screened regularly for diabetes. Lifestyle behaviors (like physical activity and diet) were also reported as well as total breastfeeding duration.

Unlike prior breastfeeding studies that relied on self-reporting of the onset of diabetes and started to follow women later in their lives, in this study women were able to be followed specifically throughout the childbearing time period and screened regularly for diabetes prior to and following pregnancies. Pre-pregnancy metabolic risk was also able to be accounted for, which included fasting glucose and insulin, obesity, perinatal outcomes, diabetes family history, and lifestyle behaviors.

Image Source: acog